"Saint Tommaso's curse"

Introduction

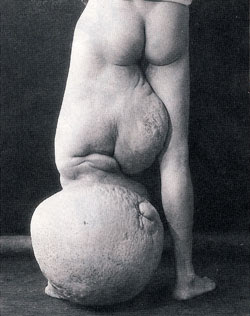

Lymphatic filariasis also known as elephantiasis is caused by parasitic worms of the Filarioidea type. Many cases of the disease have no symptoms. Some however develop large amounts of swelling of the arms, legs, or genitals. The skin may also become thicker and pain may occur. The changes to the body can result in social and economic problems for the affected person. The most spectacular symptom of lymphatic filariasis is "elephantiasis", edema with thickening of the skin and underlying tissues, which was the first disease discovered to be transmitted by mosquito bites. Elephantiasis results when the parasites lodge in the lymphatic system. The subcutaneous worms present with skin rashes, urticarial papules, and arthritis, as well as hyper, and hypopigmentation macules. Onchocerca volvulus manifests itself in the eyes, causing "river blindness" (onchocerciasis), one of the leading causes of blindness in the world. Serous cavity filariasis presents with symptoms similar to subcutaneous filariasis, in addition to abdominal pain, because these worms are also deep-tissue dwellers.

Elephantiasis leads to marked swelling of the lower half of the body.

Reference: Lymphatic filariasis

History

- Lymphatic filariasis is thought to have affected humans since about 4000 years ago. Artifacts from ancient Egypt (Mentuhopet II) (2000 BC) and the Nok civilization in West Africa (500 BC) show possible elephantiasis symptoms. The first clear reference to the disease occurs in ancient Greek literature, where scholars differentiated the often similar symptoms of lymphatic filariasis from those of leprosy.

- The first documentation of symptoms occurred in the 16th century, when Jan Huyghen van Linschoten wrote about the disease during the exploration of Goa. He noticed that the descendants of those who "had killed St. Thomas (a legend says that it was the first evangelizer of India and martyred) were all born with a lower limb, swollen from the knee down, similar to the leg of an elephant "; Therefore, lymphatic filariasis was known as the "curse of St. Thomas." Similar symptoms were reported by subsequent explorers in areas of Asia and Africa, though an understanding of the disease did not begin to develop until centuries later.

- In 1866, Timothy Lewis, building on the work of Jean-Nicolas Demarquay and Otto Henry Wucherer, made the connection between microfilariae and elephantiasis, establishing the course of research that would ultimately explain the disease.

- Nel 1871 Timothy Lewis, a Calcutta in India, scoprì la presenza di microfilarie nel sangue periferico di un paziente indiano affetto da elefantiasi.

*In 1876, Joseph Bancroft discovered the adult form of the worm. In 1877, the lifecycle involving an arthropod vector was theorized by Patrick Manson, who proceeded to demonstrate the presence of the worms in mosquitoes. Manson incorrectly hypothesized that the disease was transmitted through skin contact with water in which the mosquitoes had laid eggs.

- In 1900, George Carmichael Low determined the actual transmission method by discovering the presence of the worm in the proboscis of the mosquito vector.

"Many people in Malabar, Nayars as well as Brahmans and their wives — in fact about a quarter or a fifth of the total population, including the people of the lowest castes — have very large legs, swollen to a great size; and they die of this, and it is an ugly thing to see. They say that this is due to the water through which they go, because the country is marshy. This is called pericaes in the native language, and all the swelling is the same from the knees downward, and they have no pain, nor do they take any notice of this infirmity."

Portuguese diplomat Tomé Pires, Suma Oriental, 1512–1515.

References: Lymphatic Filariasis Discovery

Etiology and Epidemiology

The worms are spread by the bites of infected mosquito. Infections usually begin when people are children. There are three types of worms that cause the disease: Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Brugia timori. Wuchereria bancrofti is the most common. The worms damage the lymphatic system. The disease is diagnosed by looking, under a microscope, at blood collected during the night. The blood should be in the form of a thick smear and stained with Giemsa. Testing the blood for antibodies against the disease may also be used.

More than 120 million people are infected with lymphatic filariasis. About 1.4 billion people are at risk of the disease in 73 countries. The areas where it is most common are Africa and Asia. The disease results in economic losses of many billions of dollars a year.

Reference: Summary of the Third Meeting of the International Task Force for Disease Eradication

Transmission mode and Life cycle

The parasites are transmitted (larval stage) by bloodsucking insects such as mosquitoes, penetrating into the body at the time of puncture. The maturation of the parasites occurs at the level of the lymphoid organs, where they reproduce at the expense of the host. Originate from the coupling numerous microfilariae (larval stage), which circulate in the blood waiting to be swallowed up by insects in search of a blood meal. The larvae then increase in mosquitoes and horseflies, acquiring skills weed within one or two weeks. Matured, the larvae migrate to the salivary glands of the animal, ready to be transmitted to the definitive host: man. Are possible, and very common phenomena of continuous re-infestation by mosquito bites repeated over time. This factor performs a very important role in the pathogenesis of the disease. The adult parasites, the typical shape of a spindle, measure from three to ten centimeters by only 0.25 to 0.1 mm. Within the organism can live for decades nestling in the lymphatic vessels. After the insect bite, the incubation period is 5-15 months, during which time the larvae are growing up to become adult worms.

Pathogenesis and Pathology

The pathology associated with lymphatic filariasis results from a complex interplay of the pathogenic potential of the parasite, the immune response of the host, and external ('complicating') bacterial and fungal infections.

While genital damage (particularly hydroceles) and lymphoedema / elephantiasis are the most recognizable clinical entities associated with lymphatic filarial infections, there are much earlier stages of lymphatic pathology and dysfunction whose recognition has only recently been made possible through ultrasonographic and lymphoscintigraphic techniques. For example, ultrasonography has identified massive lymphatic dilatation around and for several cm beyond adult filarial worms which, though they are in continuous vigorous motion, remain 'fixed' at characteristic sites within lymphatic vessels.

Histologically, dilatation and proliferation of lymphatic endothelium can be identified, and the abnormal lymphatic function associated with these changes can be readily documented by lymphoscintigraphy. Interestingly, despite the earlier paradigm that pathology associated with lymphatic filarial diseases was primarily the result of immune-mediated inflammatory responses, all of these changes can occur in the absence of such overt inflammatory responses and, even by themselves, can lead to both lymphoedema and hydrocele formation. The immune system during the development of this 'non-inflammatory pathology' is to keep itself 'down-regulated' through the production of contra-inflammatory immune molecules; specifically, the characteristic mediators of Th2-type T-cell responses (IL-4, IL-5, IL-10) and antibodies of the IgG4 (non-complement-fixing) subclass that serve as "blocking antibodies". Such adaptations do, of course, serve to promote the biological principle of parasitism in which a satisfactory balance between parasite 'aggressiveness' and host responsiveness must evolve to maintain this special relationship.

- Grade I: lymphedema simple subcutaneous tissue.

- Grade II: Significant edema of the subcutaneous tissue.

- Grade III: hypertrophy of subcutaneous adipose tissue, with thickening of the skin (pachydermia) and loss of elasticity.

- Grade IV: myxomatous subcutaneous lymphatic infiltration with subcutaneous fibrosis.

- Grade V: severe fibrosis of the dermis with hyperkeratosis and gross deformation of the structures affected.

Reference: S. Tommaso's curse: Pathogenesis and Pathology

Clinical manifestations

The development of lymphatic filariasis in humans remains an enigma: while the infection is generally acquired early in childhood, the disease may take years to manifest itself. Indeed, many people never have outward clinical manifestations of their infection. Studies have shown that such seemingly healthy patients may have hidden lymphatic pathology. Asymptomatic infection is frequently characterized by the presence of thousands or millions of larval parasites (microfilariae) in the blood and of adult worms in the lymphatic system.

The most severe symptoms of chronic disease generally appear in adults, and in males more often than in females. In endemic communities, some 10–50% of men suffer genital damage, notably hydrocele (fluid-filled enlargement of the sacs around the testes) and elephantiasis (gross enlargement) of the penis and scrotum. Elephantiasis of the entire leg or arm, the vulva and the breast may affect up to 10% of men and women in these communities.

Acute episodes of local inflammation involving the skin, lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels often accompany chronic lymphoedema or elephantiasis. Some of these episodes are caused by the body’s immune response to the parasite, but most are the result of bacterial skin infections, linked to the partial loss of the body’s normal defences as a result of underlying lymphatic damage. Careful cleansing is extremely helpful in healing the infected areas and in both slowing and, more remarkably, reversing much of the overt damage that has already occurred.

In endemic areas, chronic and acute manifestations of filariasis tend to develop more often and sooner in refugees or newcomers than in local populations. Lymphoedema may develop within 6 months and elephantiasis as quickly as a year after arrival.

The clinical course of lymphatic filariasis is broadly divided into the following:

- Asymptomatic microfilaremia: Patients with microfilaremia are generally asymptomatic, although those with heavy microfilarial loads may develop acute and chronic inflammatory granulomas secondary to splenic destruction; passage of cloudy, milklike urine may denote chyluria.

- Acute phases of adenolymphangitis (ADL)

- Chronic, irreversible lymphedema

Lymphatic filariasis symptoms predominantly result from the presence of adult worms residing in the lymphatics. They include the following:

- Fever

- Inguinal or axillary lymphadenopathy

- Testicular and/or inguinal pain

- Skin exfoliation

- Limb or genital swelling

The following acute syndromes have been described in filariasis:

- Acute ADL

- Filarial fever - Characterized by fever without associated adenitis

- Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia (TPE)

Acute ADL

This refers to the sudden onset of febrile, painful lymphadenopathy. Pathologically, the lymph node is characterized by a retrograde lymphangitis, distinguishing it from bacterial lymphadenitis. Symptoms usually abate within 1 week, but recurrences are possible.

Signs and symptoms of ADL include episodic attacks of fever associated with inflammation of the inguinal lymph nodes, testis, and spermatic cord, as well as with lymphedema. Skin exfoliation of the affected body part usually occurs with resolution of an episode.

Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia

TPE is a form of occult filariasis. Presenting symptoms include a dry, paroxysmal cough; wheezing; dyspnea; anorexia; malaise; and weight loss.

Symptoms of TPE are usually due to the inflammatory response to the infection. Characteristically, peripheral blood eosinophilia and abnormal findings on chest radiography are observed. TPE is usually related to W bancrofti or B malayi infection.

Reference: History of Lymphatic filariasis

Diagnosis

- Microbiological examination: The standard method for diagnosing active infection is the identification of microfilariae in a blood smear by microscopic examination. The microfilariae that cause lymphatic filariasis circulate in the blood at night (called nocturnal periodicity). Blood collection should be done at night to coincide with the appearance of the microfilariae, and a thick smear should be made and stained with Giemsa or hematoxylin and eosin. For increased sensitivity, concentration techniques can be used.

- Serologic techniques: provide an alternative to microscopic detection of microfilariae for the diagnosis of lymphatic filariasis. Patients with active filarial infection typically have elevated levels of antifilarial IgG4 in the blood and these can be detected using routine assays.

Because lymphedema may develop many years after infection, lab tests are most likely to be negative with these patients.

- Diagnostic imaging:

- Traditional radiology, the diagnosis of elephantiasis is clinical and requires no radiographic confirmation. At X-ray of long bones may show thickening of the cortex for wavy periosteal new bone formation in response to lymphedema and obstruction of the venous circulation. However, we should not exclude the possibility of complications osteomielitiche, especially in the advanced stages of elephantiasis. A sedentary lifestyle to which they are often forced individuals suffering from elephantiasis may cause focal osteoporosis of the lower limbs (Sudeck's osteodystrophy).

- Lymphangiography, the traditional lymphangiography employs oily contrast media that are injected from the feet, in pots collectors are identified and prepared previously by a surgeon. The contrast highlights the X-ray the course of lymphatic vessels, which when they are pathological, are dilated, tortuous, and when they are broken, have collateral circulation. Lymphoscintigraphy uses radiopharmaceuticals that are injected subcutaneously, in the area that is drained by the lymphatic vessels to be studied: the radioisotope used is 99mTc-sulfide. The exam is easier to perform, less invasive, less dangerous and gives a more accurate anatomical and functional, but it costs much more than the traditional lymphangiography. Often the result is not related to the clinical presentation of the disease: the linfoscintigramma often show abnormal findings in most parts of the body apparently less "sick". A large group of patients with micorfilariemia, but asymptomatic show an important increase in the inguinal lymph flow, from the lower limbs.

- Ultrasound, Ultrasound may reveal the adult heartworms in the main superficial inguinal lymph vessels, the area of the scrotum in males and breast and axillary lymph nodes in females, allowing early diagnosis of infection and disease, especially in pediatric cases . Ultrasound can demonstrate the tortuosity of the scrotal lymphatics, with expansion up to 15mm caliber. The ultrasound examination can already at this stage to highlight the movements of adult heartworms in dilated lymphatic vessels. Ultrasound can also be used in the study of breast adulthood. Filariasis breast can present with solitary nodules; can be diagnosed by cytology from the lesion by US-guided puncture and aspiration: the finding of microfilariae lymphadenitis can avoid surgery more challenging.

References: Lymphatic filariasis: Guidance for evaluation and treatment;

Lymphatic filariasis: diagnosis and pathogenesis. WHO expert committee on filariasis

Prognosis and Treatment

- About 40 million disfigured and incapacitated by the disease. Elephantiasis caused by lymphatic filariasis is one of the most common causes of disability in the world. In endemic communities, approximately 10 percent of women can be affected with swollen limbs and 50 percent of men can have from mutilating genital disease. In areas endemic for podoconiosis, prevalence can be 5% or higher.

- Treatments for lymphatic filariasis differ depending on the geographic location of the endemic area. In sub-Saharan Africa, albendazole is being used with ivermectin to treat the disease, whereas elsewhere in the world, albendazole is used with diethylcarbamazine. Geo-targeting treatments is part of a larger strategy to eventually eliminate lymphatic filariasis by 2020.

- Another form of effective treatment involves rigorous cleaning of the affected areas of the body. Several studies have shown that these daily cleaning routines can be an effective way to limit the symptoms of lymphatic filariasis. The efficacy of these treatments suggests that many of the symptoms of elephantiasis are not directly a result of the lymphatic filariasis but rather the effect of secondary skin infections.

- In addition, surgical treatment may be helpful for issues related to scrotal elephantiasis and hydrocele. However, surgery is generally ineffective at correcting elephantiasis of the limbs.

A vaccine is not yet available but is likely to be developed in the near future.

Treatment for podoconiosis consists of consistent shoe-wearing (to avoid contact with the irritant soil) and hygiene - daily soaking in water with an antiseptic (such as bleach) added, washing the feet and legs with soap and water, application of ointment, and in some cases, wearing elastic bandages. Antibiotics are used in cases of infection.

In 2003 it was suggested that the common antibiotic doxycycline might be effective in treating lymphatic filariasis. The parasites responsible for elephantiasis have a population of symbiotic bacteria, Wolbachia, that live inside the worm. When the symbiotic bacteria are killed by the antibiotic, the worms themselves also die.

References: Lymphatic filariasis: Guidance for evaluation and treatment

Lymphatic filariasis: Prognosis