Written by: Eleonora Giulianotti, Eugenia Limerutti, Anna V.Solia

Definition

Addison’s disease (also chronic adrenal insufficiency, hypocortisolism, and hypoadrenalism) is a rare, chronic endocrine disorder in which the adrenal glands do not produce sufficient steroid hormones (glucocorticoids and often mineralocorticoids). It is characterised by a number of relatively nonspecific symptoms, such as abdominal pain and weakness, but under certain circumstances these may progress to Addisonian crisis, a severe illness in which there may be very low blood pressure and coma.

The condition arises from problems with the adrenal gland itself, a state referred to as “primary adrenal insufficiency” and can be caused by damage by the body’s own immune system, certain infections or various rarer causes. Addison’s disease is also known as chronic primary adrenocortical insufficiency, to distinguish it from acute primary adrenocortical insufficiency, most often caused by Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome. Addison’s disease should also be distinguished from secondary and tertiary adrenal insufficiency which are caused by deficiency of ACTH (produced by the pituitary gland) and CRH (produced by the hypothalamus) respectively. Despite this distinction, Addisonian crisis can happen in all forms of adrenal insufficiency.

Addison’s disease and other forms of hypoadrenalism are generally diagnosed via blood tests and medical imaging. Treatment involves replacing the absent hormones (oral hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone). Lifelong, continuous treatment with steroid replacement therapy is required, with regular follow-up treatment and monitoring for other health problems.

Epidemiology

The frequency rate of Addison’s disease in the human population is sometimes estimated at roughly 1 in 100,000. Some research and information sites put the number closer to 40-60 cases per 1 million population. (1/25,000-1/16,600). Determining accurate numbers for Addison’s is problematic at best and some incidence figures are thought to be underestimates.

Addison’s can afflict persons of any age, gender, or ethnicity, but it typically presents in adults between 30 and 50 years of age.

Research has shown no significant predispositions based on ethnicity.

Symptoms

The symptoms of adrenal insufficiency usually begin gradually. Worsening chronic fatigue and muscle weakness, loss of appetite and weight loss are characteristic of the disease. Nausea, vomiting and diarrhea occur in about 50 percent of all cases. Blood pressure is low and falls further when standing, causing dizziness or fainting.

Skin changes are also common in Addison’s disease, with areas of hyperpigmentation (or dark tanning) covering exposed and nonexposed parts of the body. This darkening of the skin is most visible on scars, skin folds and pressure points, such as the elbows, knees, knuckles, toes, lips and mucous membranes.

Addison’s disease can cause irritability and depression. Because of salt loss, craving of salty foods is also common. Hypoglycemia (or low blood sugar) is more severe in children than in adults. In women, menstrual periods may become irregular or stop completely.

Because the symptoms progress slowly, they are usually ignored until a stressful event like an illness or an accident causes them to become worse. This is called an Addisonian crisis, or acute adrenal insufficiency. In most patients, symptoms are severe enough to seek medical treatment before a crisis occurs. However, in 25 percent of all patients, symptoms do not appear until an Addisonian crisis. Symptoms of an Addisonian crisis include sudden penetrating pain in the lower back, abdomen or legs, severe vomiting and diarrhea, followed by dehydration, low blood pressure, loss of consciousness, hypoglycemia, confusion, psychosis, slurred speech, lethargy, hyponatriemia, hypercalcemia, convulsions and fever.

Diagnosis

ACTH stimulation test:

In suspected cases of Addison’s disease, one needs to demonstrate that adrenal hormone levels are low even after appropriate stimulation (called the

ACTH stimulation test) with synthetic pituitary

ACTH hormone tetracosactide. Two tests are performed, the short and the long test.

The short test compares blood cortisol levels before and after 250 micrograms of tetracosactide (IM/IV) is given. If, one hour later, plasma cortisol exceeds 170 nmol/L and has risen by at least 330 nmol/L to at least 690 nmol/L, adrenal failure is excluded. If the short test is abnormal, the long test is used to differentiate between primary adrenal insufficiency and secondary adrenocortical insufficiency.

The long test uses 1 mg tetracosactide (IM). Blood is taken 1, 4, 8, and 24 hours later. Normal plasma cortisol level should reach 1000 nmol/L by 4 hours. In primary Addison’s disease, the cortisol level is reduced at all stages whereas in secondary corticoadrenal insufficiency, a delayed but normal response is seen.

Distinguish between primary and secondary insufficiency by measuring the

ACTH level:

- Primary insufficiency : ACTH increate

- Secondary insufficiency : ACTH decreased

CRH stimulation test:

CRH is the acronym for corticotropin-releasing hormone.

CRH causes the pituitary gland to secrete

ACTH, which in turn causes the adrenal glands to secrete cortisol.

To begin the

CRH stimulation test, your doctor will draw some blood and measure the cortisol level. Next, synthetic

CRH is injected into your bloodstream. Blood cortisol is measured every 30 minutes for about an hour and a half after the injection.

Possible

CRH stimulation test results:

- If CRH injection causes an ACTH response, but no cortisol response, the pituitary is functioning but the adrenal glands are not. Such results are consistent with the diagnosis of primary adrenal insufficiency or Addison’s disease.

- If CRH injection does not generate ACTH response, the problem is the pituitary gland (secondary adrenal insufficiency).

- CRH injection produces a delayed ACTH response, the problem is the hypothalamus.

Imaging:

Other tests that may be performed to distinguish between various causes of hypoadrenalism are renin and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels, as well as medical imaging – usually in the form of ultrasound, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Other investigations:

- Insulin tolerance test1 – hypoglycaemia is induced by an insulin infusion and the cortisol response is monitored; this is not regularly performed due to safety issues

- Adrenal autoantibodies – if negative, consider investigating for other causes, e.g. tuberculosis

- ECG – PR and QT interval prolongation

- CXR – lung neoplasm

- Abdominal X-ray – any adrenal calcification which may indicate previous TB infection

- Specific investigations, e.g. CT scan of adrenals

- It may be appropriate to test other hormones of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, e.g. TSH, prolactin, FSH/LH

Pathogenesis

Autoimmune Addison’s disease is caused by autoreactivity towards the adrenal cortex involving 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies and autoreactive T cells. Autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex is triggered by hitherto unknown environmental factors in individuals with genetic susceptibility. Several genes have been identified, of which the major histocompatibility complex haplotypes DR3-DQ2 and DR4-DQ8 are most strongly associated. In addition, other genes also implicated in other autoimmune diseases are linked to Addison’s disease, such as cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 22 (PTPN22), major histocompatibility complex class II transactivator (CIITA), and most recently the C-lectin type gene (CLEC16A). Studies employing T cells in humans and animal models, and the collection of large patient cohorts facilitating genome-wide screening projects, will hopefully improve the understanding of the pathogenesis of the disease in the near future.

Risk factors

Risk factors for the autoimmune type of Addison’s disease include other autoimmune diseases:

- Family history of Addison’s disease

Possible Complications

Complications of Addison’s disease include:

- Corticosteroid medication side effects:

- Cataracts

- Delayed wound healing

- Excess hair growth

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

- High blood pressure

- Increased appetite

- Insomnia

- Gastritis

- Swelling

- Stomach ulcers

- Weakness

- Weakening of the bones

- Weakening of the immune system

- Hyperkalemia

- High body temperature

Complications also may result from the following related illnesses:

Therapy

Manteinance:

Treatment for Addison’s disease involves replacing the missing cortisol, sometimes in the form of hydrocortisone tablets, or prednisone tablets in a dosing regimen that mimics the physiological concentrations of cortisol. Alternatively one quarter as much prednisolone may be used for equal glucocorticoid effect as hydrocortisone. Treatment must usually be continued for life. In addition, many patients require fludrocortisone as replacement for the missing aldosterone. Caution must be exercised when the person with Addison’s disease becomes unwell with infection, has surgery or other trauma, or becomes pregnant. In such instances, their replacement glucocorticoids, whether in the form of hydrocortisone, prednisone, prednisolone, or other equivalent, often need to be increased. Inability to take oral medication may prompt hospital attendance to receive steroids intravenously. People with Addison’s are often advised to carry information on them (e.g. in the form of a MedicAlert bracelet) for the attention of emergency medical services personnel who might need to attend to their needs.

It also seems that treatment with DHEA (25-50 mg / day) may improve the “well-being” and sexuality, the BMD in women and protect the cardiovascular system.

Crisis:

Standard therapy involves intravenous injections of glucocorticoids and large volumes of intravenous saline solution with dextrose (glucose), a type of sugar. This treatment usually brings rapid improvement. When the patient can take fluids and medications by mouth, the amount of glucocorticoids is decreased until a maintenance dose is reached. If aldosterone is deficient, maintenance therapy also includes oral doses of fludrocortisone acetate.

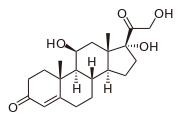

prednisone

cortisol

fludrocortisone

Natural remedies:

Other treatments for Addison’s disease include natural and holistic remedies which can be effective in assisting with the relief of symptoms as well as addressing the individual’s overall health and well being.

Herbal and homeopathic remedies are gentle, yet effective – without the harmful side effects of conventional medicine. A combination of herbs such as Borago officinalis (Borage), Eleutherococcus senticosis (Siberian Ginseng) and Astragalus membranaceous (Huang Qi) supports the functioning of the adrenal glands and helps to assist the body to fight the stress of modern day living.

Ginger (which stimulates digestion and acts as an anti-nausea aid to treat symptoms of nausea and vomiting) can be beneficial in lessening the symptoms of Addison’s disease. Siberian ginger is particularly effective as a general tonic and helps to relieve physical and emotional stress, while liquorice enhances the activity of mineralocorticoids. Consult a homeopath or herbalist about remedies for your

Complementary therapies:

- Meditation

- Yoga

- Tai Chi

- Acupuncture