Dainese Cristina

Ferrero Anna

Description

Menthol is made synthetically or obtained from cornmint, peppermint or other mint oils. Mentha arvensis is the primary species of mint used to make natural menthol crystals and natural menthol flakes. (−)-Menthol occurs naturally in peppermint oil obtained from Mentha x piperita. The biosynthesis of (−)-menthol takes place in the secretory gland cells of the peppermint plant. It can be extracted from the leaves by distillation, but is more commonly made synthetically.

Classification

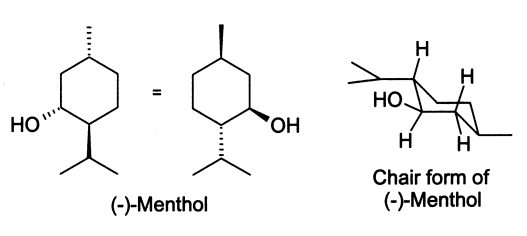

Menthol is an organic compound with the chemical formula C10H20O. It is a waxy, crystalline substance, clear or white in color, which is solid at room temperature and melts slightly above. The main form of menthol occurring in nature is (−)-menthol (also called l-menthol or (1R,2S,5R)-menthol).

Indications

Menthol can be melted with warm and readily produces a smelling vapor. Although it is of very low toxicity, it has a number of noticeable effects on the body, which have led to a variety of therapeutic uses.

Menthol's ability to chemically trigger the cold-sensitive TRPM8 receptors in the skin is responsible for the cooling sensation it provokes when inhaled, eaten, or applied to the skin. The compound does not actually change the skin’s temperature, but merely produces a feeling of cold.

Another important property of this compound is that it can act as a counterirritant, that is a substance that causes mild irritation or inflammation in one place, distracting attention from pain in another.

The anesthetic properties of menthol are thought to be due to the fact that it binds to kappa opioid receptors, they help control the perception of pain.

Menthol is included in many products, the compound is widely used in cough and cold remedies because of its soothing effects and as a flavoring in candy, chewing gum, medical products and cigarettes. It is also used in products intended to relieve skin irritation, sore throat, or nasal congestion, to treat sunburn, fever, or muscle aches. Most products used to relieve these conditions contain only small amounts of the compound.

Menthol cigarette and side effects

Because of its ability to mask smoke harshness and irritation from nicotine, menthol has become a popular cigarette choice. Menthol is not only used in cigarettes as a flavour additive, tobacco companies know that menthol also has sensory effects and interacts with nicotine. The companies manipulate menthol’s ability to mask the harshness, increase the ease of smoking and provide a cooling sensation to provide particular sensory effects and to minimise the immediate negative effects of tobacco smoke (harshness, irritation) and superimpose positive attributes (coolness, smoothness) to make menthol cigarettes easier to inhale.

In the cigarette market in the United States, one quarter of cigarettes are labeled “menthol”. Menthol is present in 90% of all tobacco products both ‘mentholated’ and ‘not mentholated’. Over 70% of African American smokers use menthol cigarettes, compared with 30% of White smokers. Further, menthol cigarettes are disproportionately preferred by adolescents, adult women, and those with low income.

Time to first cigarette is a very robust, reliable indicator of strength of nicotine dependence. Those smokers who have their first cigarette of the day soon after waking up ( ≤ 5 min) are considered to be more nicotine dependent than those who wait longer. Different data suggest that menthol cigarettes use may be associated with heavier nicotine dependence:

- In a study of female smokers, smokers of menthol cigarettes had a shorter time to the first cigarette of the day as compared to non-menthol smokers (19.0 minutes and 37.4 minutes, respectively).

- A retrospective cohort analysis of patients of a cessation clinic found that 24.3% of menthol smokers had their first cigarette within 5 minutes upon waking as compared to 19.9% of non-menthol smokers.

- Comparing Black/African American smokers with White smokers in an observational study, other researchers found that, on average, Black/African American smokers reported a shorter time to first cigarette after waking.

- A national school-based survey of adolescents in grades 6 through 12 was used to assess the relationship between menthol cigarette use and nicotine dependence in youth: teens who regularly smoked menthol cigarettes had 45% greater odds of scoring higher on a nicotine dependence scale than teens who regularly smoked non-menthol cigarettes. Smokers may find it easier to inhale more deeply from menthol cigarettes and therefore take in more nicotine.

- Another study also examined measures of nicotine dependence among adolescent smokers who were already established smokers. Compared with smokers of non menthol cigarettes, smokers of menthol cigarettes were more likely to report symptoms of dependence, such as needing a cigarette less than one hour after smoking and experiencing craving after not smoking for a few hours. The researchers concluded that young smokers of menthol cigarettes may experience greater withdrawal and addiction symptoms as compared to young smokers who smoke non-menthol cigarettes.

- A cross-sectional study was conducted among women smokers. Women menthol smokers show increased evidence of tobacco dependence, including smoking their first cigarette within five minutes of waking and having a history of shorter previous quit attempts.

Taken together, these data indicate that menthol smokers have greater nicotine dependence and may find it more difficult to quit smoking.

A cross-sectional study on tobacco use and dependence among woman: does menthol matter?, 2012

Menthol cigarette smoking and nicotine dependence, 2011

Menthol attenuates respiratory irritation responses to multiple cigarette smoke irritants

Inhaled menthol exerts complex olfactory and sensory effects by interacting with olfactory and somatosensory neurons and respiratory tissues. The cooling sensation elicited by inhaled menthol is likely mediated via neuronal transient receptor potential melatonin 8 (TRPM8) ion channels expressed in somatosensory neurons innervating the airways. Activation of TRPM8 by cold or menthol results in an increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration and menthol-induced release from intracellular Ca2+ stores has been shown to enhance neurotransmission at sensory synapses.

Menthol is not selective toward TRPM8 and was shown to interact with other sensory targets. Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 TRPA1 is expressed in a subset of trigeminal and dorsal root neurons, TRPA1 is usually involved in signaling induced by irritant and inflammatory substances. Menthol caused a mild irritation response, depending on activation of trigeminal TRPA1 channels by a CYP450-generated metabolite. The structure of the menthol metabolite is not known, however, since TRPA1 is sensitive to electrophiles, it is likely that the metabolite is electrophilic.

The counterirritant effect is due to the activation of TRPM8 receptors but not TRPA1 receptors. The parent compound menthol is the active counterirritant.

Cigarette smoke contains numerous irritants that stimulate chemosensory nerves. Stimulation of these nerves initiates important defense mechanisms, leading to unpleasant burning, tingling, and itching sensations and reflex responses, such as coughing or sneezing.

Acrolein is a potent irritant in cigarette smoke that induces sensory irritation and cough, it activates chemosensory nerves via the TRPA1 irritant receptor. At 4 ppm, menthol did not attenuate the irritant response to acrolein, at 16 ppm menthol blocked the irritant response to acrolein. So the counterirritant effects of menthol are apparent at concentration below to those present in mentholated cigarette smoke (menthol concentration in mentholated cigarette smoke is 8 μM, equivalent to 200 ppm).

In addition to acrolein, cigarette smoke contains acidic and volatile organic irritant constituents like acetic acid and cyclohexanone, which act through acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs), TRPV1 receptors, and other sensory receptor classes. Menthol partially attenuated the irritation response to both acetic acid and cyclohexanone, indicating that its counterirritant effects are likely generalized in nature, and not specific to irritants which acted through TRPA1.

Experiments were designed to investigate the role of TRPM8 in menthol-induced counterirritation. l-menthol strongly attenuated the sensory irritation response to acrolein. This effect was significantly diminished in animals treated with AMTB, the TRPM8 antagonist.

Studies have shown that, at high concentrations, menthol is an antagonist of murine TRPA1 channels. TRPA1 antagonism may contribute to the counterirritant effects of menthol against acrolein but cannot explain the counterirritant effects against cyclohexanone and acetic acid.

Menthol is a TRPM8 agonist, and TRPM8 stimulation is thought to exert analgesic and/or local anesthetic effects, suggesting that this pathway may be involved in the counterirritancy. The mechanism through which TRPM8 activation in trigeminal nerve endings leads to inhibition of respiratory irritation responses is unknown. It is possible that this mechanism is related to mechanisms mediating the analgesic effects of menthol. Studies suggested that menthol application leads to central inhibition of nociceptor input from DRG in the spinal cord. Other studies suggest that menthol causes presynaptic inhibition of sensory fibers coexpressing TRPM8 with proalgesic receptors. Both peripheral and central mechanisms of menthol inhibition of the respiratory irritation response need to be explored.

These results provide evidence that menthol is present in pharmacologically effective counterirritant concentrations in mentholated cigarette smoke. By decreasing the unpleasant chemosensory responses to the irritants present in cigarette smoke through direct interaction with chemosensory nerves, menthol may facilitate smoke inhalation, thereby promoting the development of nicotine addiction and smoking-related morbidities.

Menthol attenuates respiratory irritation responses to multiple cigarette smoke irritants, 2011

Menthol effects on nicotine receptors in sensory neurons

Psychophysical studies showed that nicotine elicits burning or stinging pain sensation on oral or nasal mucosa and these sensations are thought to involve activation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) expressed in the sensory fibers innervating these tissues. Intraepithelial free nerve endings of the trigeminal nerve innervate the oral and upper respiratory tract and convey sensations from the mucosa and have been shown to express most genes encoding the major neuronal nAChR subunits (α2–α7, α9, and β2–β4).

Interaction between menthol and nAChRs on human sensory perception was demonstrated: nicotine-induced irritation on tongue was significantly reduced by menthol pretreatment (cross-desensitization).

The possibility exists that menthols broadband counterirritant action as also affects nAChRs. Alternatively, menthol could directly affect nAChRs to downregulate their function.

In one study, it has been found that nAChR receptor currents were reversibly inhibited by (−) menthol in a concentration-dependent manner. The strategy of the study was using human α4β2 nAChRs stably transfected in HEK tsA201 cells. Cells were examined using the patch-clamp technique.

It was examined the effect of menthol on whole-cell currents through nAChR in sensory neurons. Individual currents were elicited by brief applications of nAChR agonist ACh or ACh/menthol mixture. When ACh (100 μM) was coapplied with menthol (100 μM), a reversible and significant reduction of the ACh-induced current amplitude was observed, without alterations in current kinetics.

To determine the dose dependence of inhibition of the nicotine-induced currents by menthol they used nicotine at 75 μM. The figure illustrates for 3 different menthol concentrations the currents induced by menthol itself and its inhibitory effect on nicotine-induced currents. Nicotine-induced currents (75 μM) were elicited following a 10 s application of either control- (black trace) or menthol-containing solution (red trace, used concentration is indicated above each trace).

nAChRs were demonstrated to be reversibly inhibited by menthol. Menthol causes an increase in single channel amplitude, a shorting of channel open time and a prolongation of its close time. The mechanism underlying the menthol-mediated inhibition of nAChR is due to a negative allosteric modulation of the nAChR. Menthol mediates its action not by blocking of the channel pore but rather via an allosteric mechanism reflected in alteration of channel gating properties.

So menthol acts as a broad-spectrum counterirritant as it reduced respiratory irritation response of several respiratory irritants found in tobacco smoke. It has a role in TRPM8 pathways through which activation of TRPM8 by menthol leads to inhibition of the respiratory irritation response. But menthol can also act as counterirritant directly at the receptor of a major irritant contained in tobacco smoke, nicotine.

Menthol Suppresses Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Functioning in Sensory Neurons via Allosteric Modulation, 2012