Iron metabolism

Mammalian cells require sufficient amounts of iron to satisfy metabolic needs and to accomplish special functions.

Iron is delivered to tissues by circulating transferrin, a transporter that captures iron released into the plasma mainly from intestinal enterocytes or reticuloendothelial macrophages.

However, iron is also potentially toxic, because, under aerobic conditions, it catalyses the propagation of ROS (reactive oxygen species).

The vast majority of body iron (at least 2.1 g) is distributed in the haemoglobin of red blood cells and developing erythroid cells and serves in oxygen transport. Significant amounts of iron are also present in macrophages (up to 600 mg) and in the myoglobin of muscles (300 mg), whereas excess body iron (1 g) is stored in the liver.

Mammals lose iron from sloughing of mucosal and skin cells or during bleeding, but do not possess any regulated mechanism for iron excretion from the body.

Therefore, balance is maintained by the tight control of dietary-iron absorption in the duodenum.

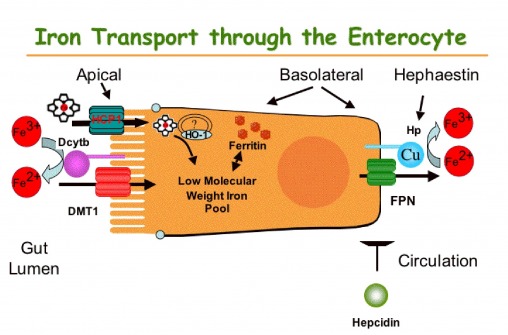

The uptake of nutritional iron involves reduction of Fe3+ in the intestinal lumen by ferric reductases such as Dcytb (duodenal cytochrome b) and the subsequent transport of Fe2+ across the apical membrane of enterocytes by DMT1 (divalent metal transporter 1).

Directly internalized or haem-derived (in this case, it is used another apical transporter called HCP1 (heme carrier protein 1) Fe2+ is processed by the enterocytes and eventually exported across the basolateral membrane into the bloodstream through the solute carrier and Fe2+ transporter ferroportin (FPN). The ferroportin-mediated efflux of Fe2+ is coupled by its reoxidation to Fe3+, catalysed by the membrane-bound ferroxidase hephaestin (Hp), that physically interacts with ferroportin.

Exported iron is scavenged by transferrin (Tf), which maintains Fe3+ in a redox-inert state and delivers it into tissues.

The Tf iron pool is replenished mostly by iron recycled from aged red blood cells and, to a lesser extent, by newly absorbed dietary iron. Senescent red blood cells are cleared by reticuloendothelial macrophages, which metabolize haemoglobin and haem and release iron into the bloodstream.

The ferroportin-mediated efflux of Fe2+ from enterocytes and macrophages into the plasma is critical for systemic iron homoeostasis. This process is negatively regulated by hepcidin, a liver-derived peptide hormone that binds to ferroportin and promotes its phosphorylation, internalization and lysosomal degradation.

Iron metabolism.

Clinical definition of sideropenic anemia

Sideropenic anemia is defined as an hypochromic microcytic anemia due to excessive loss, deficient intake or poor absorption of iron.

When examined under a microscope, the red blood cells (RBCs) appear pale or light colored because of the absence of heme, the major component of hemoglobin.

Clinical definition of sideropenic anemia

Diagnosis of sideropenic anemia

To diagnose iron deficiency anemia, the doctor may run tests to look for:

1) red blood cells color and size: with iron deficiency anemia, red blood cells are paler in color and smaller than normal;

2) hematocrit: this is the percentage of the blood volume made up by red blood cells. Normal levels are generally between 34.9 and 44.5 percent for adult women and 38.8 to 50 percent for adult men;

3) hemoglobin: lower than normal hemoglobin levels indicate anemia. The normal hemoglobin range is generally defined as 13.5 to 17.5 grams (g) of hemoglobin per deciliter (dL) of blood for men and 12.0 to 15.5 g/dL for women. The normal ranges for children vary depending on the child's age and sex;

4) ferritin: a low level of ferritin usually indicates a low level of stored iron;

5) serum iron: measures how much iron is circulating in the blood and is lower than normal in a person with iron deficiency anemia;

6) total iron binding capacity (TIBC or transferrin): measurea the amount of transferrin in the blood that is capable of transporting iron to RBCs or body stores and is higher than normal in a person with iron deficency anemia;

7) transferrin saturation: measures the percentage of iron-binding sites on transferrin that are occupied by iron and is lower that normal in a person with iron deficiency anemia.

Diagnosis of sideropenic anemia

Symptoms of sideropenic anemia

Many people with iron deficiency anemia have no symptoms at all.

Of those who do, the most common symptoms include:

1) Weakness

2) Headache

3) Irritability

4) Fatigue

5) Difficulty exercising (due to shortness of breath and rapid heartbeat).

Less common symptoms of iron deficiency include brittle nails, sore tongue and restless legs syndrome.

Symptoms of sideropenic anemia

Clinical definition of irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a heterogeneous condition characterized by the presence of abdominal discomfort or pain and bowel habit alterations: constipation (C-IBS), diarrhea (D-IBS) or alternating C and D (A-IBS).

Its clinical course is poorly known.

Patients with IBS show the ROME III criteria, that are the red flags for this disease.

They include:

1) rectal bleeding;

2) iron deficiency anemia (IDA);

3) weight loss;

4) family history of colon cancer;

5) fever;

6) age of onset after 50.

Some people are more likely to have IBS including:

1) women;

2) people with a family member who has IBS.

Moreover, women with IBS may have more symptoms during their menstrual periods.

Clinical definition of irritable bowel syndrome

Clinical definition of irritable bowel syndrome

Clinical definition of irritable bowel syndrome

Patients with IBS commonly complain that specific dietary misadventures contribute to their symptoms of abdominal discomfort, bloating, or exaggerated gastric-colic reflex. The truth is that no specific food is likely the culprit because true food allergies are rare. It is merely the act of eating that most likely initiates these postprandial symptoms.

Patients may begin to associate ingestion of certain foods such as fatty foods, caffeine, alcoholic beverages, carbonated foods or gas-producing foods as the etiology of their complaints.

The physician does not want to restrict the patients’ diet excessively because of the risk of encountering nutritional deficiencies.

However, it may be a good idea to instruct the patient to limit suspected foods and slowly reintroduce these items individually to see if similar symptoms reoccur.

Clinical definition of irritable bowel syndrome

How irritable bowel syndrome can cause sideropenic anemia

Poor absorption of iron may result from surgical removal of the stomach (gastrectomy), from intestinal disorders that cause chronic diarrhea or from abnormal food habits. Also intestinal bacteria or parasites such as hookworm can cause iron deficiency.

The important question underlying anemia is "Why do you have low iron?"

The answer may be that you don’t absorb it well. People with IBS and related digestive problems often have a problem absorbing nutrients. This is particularly obvious with diarrhea, which is clearly a malabsorption issue.

However, the same problem absorbing nutrients can also happen with constipation.

This is why many people with IBS also suffer from chronic anemia. They are not absorbing the iron that is in their food. Their digestive problem can lead to other problems such as anemia. Correcting the IBS allows the digestive tract to heal and will result in a much better absorption of these nutrients. It will also result in a much better absorption of other nutrients that are not so commonly measured.

How irritable bowel syndrome can cause sideropenic anemia

How irritable bowel syndrome can cause sideropenic anemia