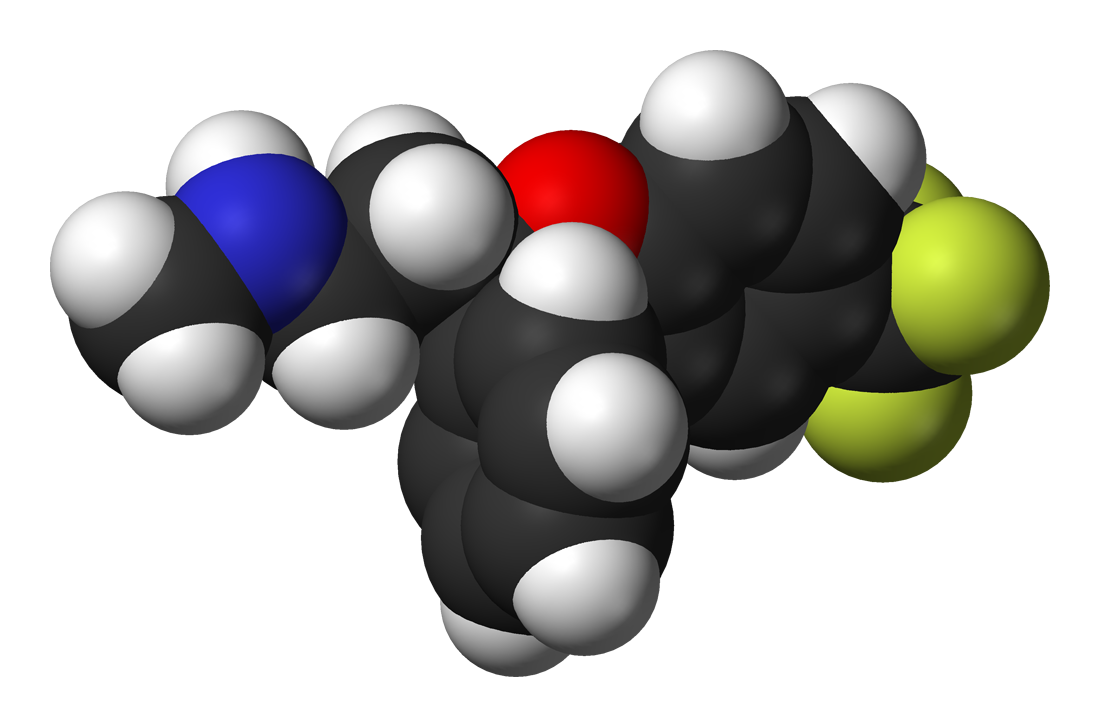

Fluoxetine(also known by the tradenames Prozac,Sarafem,Fontex,among others) is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class.

Medical uses

Fluoxetine is frequently used to treat major depression,obsessive compulsive disorder,bulimia nervosa,panic disorder,body dysmorphic disorder,premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and trichotillomania.Caution should be taken when using any SSRI for bipolar disorder as this can increase the likelihood of mania; however, fluoxetine can be used with an antipsychotic(such as quetiapine) for bipolar.It has also been used for cataplexy,obesity, and alcohol dependence,as well as binge eating disorder.

Mechanism of action

A serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) is a type of drug that acts as a reuptake inhibitor for the neurotransmitter serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)) by blocking the action of the serotonin transporter (SERT).This in turn leads to increased extracellular concentrations of serotonin and, therefore, an increase in serotonergic neurotransmission.

Fluoxetine's mechanism of action is predominantly that of a serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Fluoxetine delays the reuptake of serotonin, resulting in serotonin persisting longer when it is released. Fluoxetine may also produce some of its effects via its potent 5-HT2C receptor antagonist effects.

Fluoxetine affects neurotransmitters, the chemicals that nerves within the brain use to communicate with each other. Neurotransmitters are manufactured and released by nerves and then travel and attach to nearby nerves. Thus, neurotransmitters can be thought of as the communication system of the brain. Serotonin is one neurotransmitter that is released by nerves in the brain. The serotonin either travels across the space between nerves and attaches to receptors on the surface of nearby nerves or it attaches to receptors on the surface of the nerve that produced it, to be taken up by the nerve and released again (a process referred to as re-uptake).

Many experts believe that an imbalance among neurotransmitters is the cause of depression. Fluoxetine works by preventing the reuptake of the neurotransmitter serotonin, by nerve cells after it has been released. Since uptake is an important mechanism for removing released neurotransmitters and terminating their actions on adjacent nerves, the reduced uptake caused by fluoxetine increases free serotonin that stimulates nerve cells in the brain. The FDA approved Fluoxetine in December 1987.

SRIs are used predominantly as antidepressants (e.g., SSRIs, SNRIs, and TCAs), though they are also commonly used in the treatment of other psychological conditions such as anxiety disorders and eating disorders.

Fluoxetine

Adverse effects

Among the common adverse effects associated with fluoxetine and listed in the prescribing information, the effects with the greatest difference from placebo are nausea (22% vs 9% for placebo),insomnia(19% vs 10% for placebo),somnolence(12% vs 5% for placebo),anorexia(10% vs 3% for placebo),anxiety(12% vs 6% for placebo), nervousness (13% vs 8% for placebo),asthenia(11% vs 6% for placebo) and tremor(9% vs 2% for placebo).Those that most often resulted in interruption of the treatment were anxiety, insomnia, and nervousness.

Adverse effects

Pharmacokinetics

The bioavailability of fluoxetine is relatively high (72%),and peak plasma concentrations are reached in 6 to 8 hours. It is highly bound to plasma proteins, mostly albumin.

Fluoxetine is metabolized in the liver by isoenzymes of the cytochrome P450 system, including CYP2D6.The role of CYP2D6 in the metabolism of fluoxetine may be clinically important, as there is great genetic variability in the function of this enzyme among people. Only one metabolite of fluoxetine, norfluoxetine (N-demethylated fluoxetine), is biologically active.

Fluoxetine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and does not appreciably inhibit norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake. Nevertheless, Eli Lilly researchers found that a single injection of a large dose of fluoxetine given to a rat also resulted in a significant increase of brain concentrations of norepinephrine and dopamine.This effect may be mediated by 5HT2a and, in particular, 5HT2c receptors, which are inhibited by higher concentrations of fluoxetine. The Eli Lilly scientists also suggested that the effects on dopamine and norepinephrine may contribute to the antidepressant action of fluoxetine. In the opinion of other researchers, however, the magnitude of this effect is unclear.The dopamine and norepinephrine increase was not observed at a smaller, more clinically relevant dose of fluoxetine. Similarly, in electrophysiological studies only larger and not smaller doses of fluoxetine changed the activity of rat's norepinephrinergic neurons. Some authors, however, argue that these findings may still have clinical relevance for the treatment of severe illness with supratherapeutic doses (60–80 mg) of fluoxetine. Among SSRIs, 'fluoxetine is the least "selective" of all the SSRIs, with a 10-fold difference in binding affinity between its first and second neural targets (i.e., the serotonin and norepinephrine uptake pumps, respectively)'.

Pharmacokinetics

Anorexia and anorexia nervosa

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by immoderate food restriction and irrational fear of gaining weight, as well as a distorted body self-perception.Due to the fear of gaining weight, people with this disorder restrict the amount of food they consume. This restriction of food intake causes metabolic and hormonal disorders.Outside of medical literature, the terms anorexia nervosa and anorexia are often used interchangeably; however, anorexia is simply a medical term for lack of appetite, and people with anorexia nervosa do not in fact, lose their appetites.Anorexia nervosa has many complicated implications and may be thought of as a lifelong illness that may never be truly cured,but only managed over time. Patients suffering from anorexia nervosa may experience dizziness, headaches, drowsiness and a lack of energy.

People with anorexia nervosa continue to feel hunger, but they deny themselves all but very small quantities of food.

Anorexia nervosa is a serious mental illness characterized by the maintenance of an inappropriately low body weight, a relentless pursuit of thinness, and distorted cognitions about body shape and weight. Anorexia nervosa commonly begins during middle to late adolescence, although onsets in both prepubertal children and older adults have been described. Anorexia nervosa has a mortality rate as high as that seen in any psychiatric illness and is associated with physiological alterations in virtually every organ system, although routine laboratory test results are often normal and physical examination may reveal only marked thinness.

People suffering from anorexia have extremely high levels of ghrelin (the hunger hormone that signals a physiological desire for food) in their blood. The high levels of ghrelin suggests that their bodies are trying to desperately switch the hunger aspect on; however, that hunger call is being suppressed, ignored, or overridden.

Patients with eating disorders are usually secretive and often come to the attention of physicians only at the insistence of others. Practitioners also should be alert for medical complications including hypothermia, edema, hypotension, bradycardia, infertility, and osteoporosis in patients with anorexia nervosa.

Haller,Eating disorders.A review and update,1992

Anorexia nervosa

Attia,Anorexia nervosa,2007

Treatment

Treatment for anorexia nervosa tries to address three main areas.

- Restoring the person to a healthy weight;

- Treating the psychological disorders related to the illness;

- Reducing or eliminating behaviours or thoughts that originally led to the disordered eating.

Treatment involves combining individual, behavioral, group, and family therapy with, possibly, psychopharmaceuticals.

The biggest challenge in treating anorexia nervosa is helping the person recognize that he or she has an illness. Most people with anorexia deny that they have an eating disorder. People often enter treatment only once their condition is serious.

The goals of treatment are to restore normal body weight and eating habits. A weight gain of 1 - 3 pounds per week is considered a safe goal.

A number of different programs have been designed to treat anorexia. Sometimes the person can gain weight by:

-Increasing social activity

-Reducing the amount of physical activity

-Using schedules for eating

Many patients start with a short hospital stay and continue to follow-up with a day treatment program.

A longer hospital stay may be needed if:

-The person has lost a lot of weight (being below 70% of their ideal body weight for their age and height).For severe and life-threatening malnutrition, the person may need to be fed through a vein or stomach tube.

-Weight loss continues even with treatment

-Medical complications, such as heart problems, confusion, or low potassium levels develop

-The person has severe depression or thinks about committing suicide

Medications such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers may help some anorexic patients when given as part of a complete treatment program. Examples include:

-Antidepressants, especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

-Olanzapine (Zyprexa, Zydis) or other antipsychotics

These medicines can help treat depression or anxiety.

Linda J. Vorvick, Anorexia Nervosa,2012

Neurobiological Hypotheses

The striking physical and behavioral characteristics of anorexia nervosa have prompted the development of a variety of neurobiological hypotheses over the years. Recently, results of several investigations have suggested that abnormalities in central nervous system serotonin function may play a role in the development and persistence of the disorder. Notably, studies of long-term weight-recovered patients have described indications of increased serotonin activity, such as elevated levels of the serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid in the cerebrospinal fluid and reduced binding potential of 5-HT2A receptors, suggestive of higher levels of circulating central nervous system serotonin, in several brain regions.

Attia,Anorexia nervosa,2007

Neurotransmitter systems implicated

Serotonergic system

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) is involved in a broad range of biological, physiological and behavioral functions. The neurotransmitter system includes tryptophan hydroxylase, the 5-HT transporter (SLC6A4 or 5-HTT) and 5-HT receptors. Several lines of evidence implicate the serotonergic system in body weight regulation and more specifically in eating behavior and eating disorders . In cerebrospinal fluid 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) levels were elevated in long-term weight-restored patients with Anorexia Nervosa (AN) in comparison with controls, suggesting that hyperserotonergic function is a trait marker in eating disorders. The increased serotonergic neurotransmission could also account for characteristic psychopathological features such as perfectionism, rigidity and obsessiveness frequently associated with AN .

Dopaminergic system

The dopaminergic system has been implicated in the pathophysiology of AN. For example, major symptoms related to AN like repulsion to food, weight loss, hyperactivity, distortion of body image, and obsessive–compulsive behavior have all been related to dopamine activity.

Leptinergic–melanocortinergic system

There has been a tremendous increase in the number of molecular genetic studies pertaining to body weight regulation in the last 15 years. Since its discovery in 1994, research has focused on leptin-mediated signaling pathways. Leptin is not only a key hormone implicated in the regulation of energy balance, but it is also a pleiotropic hormone involved in various neuroendocrine and behavioral alterations associated with profound changes in energy storage, including the adaptation of the organism to semi-starvation.

Hypoleptinemia is a cardinal feature of acute AN, and in most studies the low leptin levels are typically below those of healthy gender- and age-matched controls and reflect the low fat mass, thus signaling energy depletion to the brain. In most studies, circulating levels of leptin were highly correlated with percent body fat and, to a lesser extent, with BMI on referral . In further studies patients who had recovered from eating disorders also had reduced serum leptin levels after adjustment for BMI and/or fat mass, suggesting that relative hypoleptinemia might be a trait marker in eating disorders.

Scherag,Eating disorders:the current status of molecular genetic research,2009

Fluoxetine and anorexia

Role of neuropeptide Y and proopiomelanocortin

Fluoxetine is an anorexic agent known to reduce food intake and weight gain. An experiment conducted by Myung team examined mRNA expression levels of neuropeptide Y (NPY) and proopiomelanocortin (POMC) in the brain regions of rats using RT-PCR and in situ hybridization techniques after 2 weeks of administering fluoxetine daily. Fluoxetine persistently suppressed food intake and weight gain during the experimental period. RT-PCR analyses showed that mRNA expression levels of both NPY and POMC were markedly reduced by fluoxetine treatment in all parts of the brain examined, including the hypothalamus. POMC mRNA in situ signals were significantly decreased, NPY levels tended to increase in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) of fluoxetine treated rats (compared to the vehicle controls). These results reveal that the chronic administration of fluoxetine decreases expression levels in both NPY and POMC in the brain, and suggests that fluoxetine-induced anorexia may not be mediated by changes in the ARC expression of either NPY or POMC. It is possible that a fluoxetine raised level of 5-HT play an inhibitory role in the orectic action caused by a reduced expression of ARC POMC (alpha-MSH).

Myung,Role of neuropeptide Y and proopiomelanocortin in fluoxetine-induced anorexia,2005

Scientists have also compared the effects of intraperitoneally administered bombesin (10-1000 nmol/kg; BOM), (dl) fenfluramine HCl (0.9-37.3 mumol/kg; fenfluramine), fluoxetine HCl (2.9-86.7 mumol/kg; fluoxetine), and d-amphetamine sulfate (0.27-10.9 mumol/kg; AMPH) on both 18-hr deprivation-induced feeding and one-bottle, taste aversion conditioning in male, Long-Evans rats.

The nonpeptidal anorectic compounds, fenfluramine,fluoxetine, and AMPH, induced both dose-related anorexia and taste aversion conditioning.

Ervin,The effects of anorectic and aversive agents on deprivation-induced feeding and taste aversion conditioning in rats,1995

Fluoxetine-induced anorexia. A behavioural profile

There has been some discussion about the extent to wich the anorectic actions of drugs enhancing serotinergic function can be differentially attributed to the enhancement of 5-HT release or inhibition of 5-HT reuptake. Fluoxetine is a potent anorectic agent.

There have been applied a series of behavioural techniques to the study of fluoxetine anorexia,both to provide a comparison with agents having less specific effects on serotinergic systems and to suggest the behavioural mechanisms producing anorexia. The analysis of the meal patterns of free-feeding animals,as in experiment 1,provides a sensitive assay of both the magnitude and duration of anorexia.Experiment 2 describes such a study of fluoxetine-induced anorexia.A final experiment examines the extent of rebound feeding after fluoxetine-induced anorexia and a possible relationship to the absence of tolerance to the anorectic effect of this drug is postulated.

In free-feeding rats a dose of 10 mg/kg reduced meal size but had no significant effect on meal frequency. Feeding rate during meals was also reduced. Direct observation of behaviour associated with eating suggested that fluoxetine did not act by enhancing sleep or other behaviour patterns that interfere with eating, although the transition from feeding to sleep occured more rapidly after drug treatment. Enhancement of satiety or interference with the sustaining of meals by fluoxetine would be consistent with these data. Rebound feeding after anorexia was not observed in either the meal pattern study or in a separate experiment using schedule fed animals. There was also no clear development of tolerance to the anorectic effect of fluoxetine, and we discuss possible reasons for an association of these two properties.

In conclusion fluoxetine led to a substantial reduction in food intake.

Clifton,A behavioural profile of fluoxetine-induced anorexia,1989

Partial reversal of fluoxetine anorexia by the 5-HT antagonist metergoline

Fluoxetine is entering widespread use as an antidepressant with clearly established acute and prophylactic utility. One advantage of this drug is a tendency to reduce food intake and body weight during treatment, rather than to produce increases in both parameters. So increase in body weight is an often-reported and undesirable side-effect of treatment with fluoxetine. The anorectic effect is typical of manydrugs that,either directly or indirectly,enhance serotonergic mechanisms and is a well established property of fluoxetine.

The experiment conducted by laboratorists of the Sussex University examined the effect on fluoxetine-induced anorexia of metergoline at a low dose and also the effect of 1 mg/kg of the selective 5 HT2 antagonist ketanserin.

Fluoxetine produced a substantial anorexia and metergoline alone had no effect on food intake.

A first experiment showed that the reduction of intake produced by 5 or 10 mg/kg fluoxetine in rats eating either a solid or a liquid meal was partially antagonised by 1 mg/kg of the 5HT1/5HT2 antagonist metergoline but not by 1 mg/kg of the 5HT2 antagonist ketanserin. The second experiment examined the meal patterning of rats given 5 mg/kg fluoxetine and 1 mg/kg metergoline. Fluoxetine alone increased the latency to feed, reduced meal size and shifted the inter-pellet interval (IPI) distribution to the right. Metergoline alone had little immediate effect on food intake or other feeding parameters but partially reversed the reduction of food intake produced by fluoxetine. There was a complete reversal of the increased latency to feed and a partial reversal of the depression of meal size. However, the rightward shift of the IPI distribution caused by fluoxetine, which indicated a depression of feeding rate, was more pronounced after combined treatment.

Lee,Partial reversal of fluoxetine anorexia by the 5-HT antagonist metergoline,1992

Conclusion

We conclude that fluoxetine reduces food intake by enhancing satiety through a serotonergic dependent mechanism but reduces feeding rate through a separate mechanism, whose neurochemical basis remains to be established.